An Aeroplane Too Far: The Avro-Whitworth AW/HS 681

This paper briefly describes the projected heavy military transport, the AW/HS 681; an aeroplane designed but never actually built by Avro-Whitworth Aircraft Limited, Coventry. To place this aeroplane in its context, it will be germane to relate the state of the British Aircraft Industry some years prior to the project’s cancellation.

At the conclusion of the Second World War the British aircraft industry was a large undertaking, its size and growth directly attributable to the requirements of that conflict. Some fifteen major airframe manufacturers and about seven aero engine companies provided the aeroplanes that contributed greatly to the allied victory. Virtually all these aircraft were for military purposes in some form or another. At the end of the war contracts were suddenly cancelled or greatly reduced and thousands of people employed in the industry were laid off or “let go” to use a modern euphemism.

Therefore, with the coming of peace the British aircraft industry was not particularly well adapted to produce aeroplanes for the civilian market; virtually all its output having been skewed towards military requirements. This was not the case in the USA, where a number of military transport aircraft had been formerly designed as civilian airliners, most notably the ubiquitous Douglas DC3, C47, or “Dakota”. Consequently, machines such as this were immediately available for the post war civilian aviation market. Therefore, the Americans had a decided edge in this sphere right from the cessation of hostilities. Some of the seeds of British lack of success in the post- war civilian airliner market were sown right here.

The problems with the British aircraft industry were manifold, throughout the post- war period of the forties, fifties and sixties. Some of the problems were directly attributable to the industry itself, but many more were of a governmental nature. For example, in 1947 the Labour administration agreed the sale of a number of Rolls Royce Nene turbojets, the world’s most advanced gas turbine at the time, to Stalin’s Soviet Union. This must rank as one of most politically stupid decisions in post war British foreign policy. When the Soviet designed Mig 15 fighter appeared in the skies over Korea, utilising a combination of seized advanced German airframe technology allied to a carbon copy of the British Nene engine, many people must have shook their heads in utter disbelief at such ineptitude. One thing became immediately apparent, the Gloster Meteor, then being used by the Royal Australian Air Force in Korea, was totally incapable of dealing with the Mig 15 in combat and was withdrawn. Parity in combat was only restored with the hurried introduction of the North American F86 Sabre.

It would be wrong, however, to infer that there were no British commercial successes in international civil aviation markets; the Vickers Armstrong Viscount medium-haul turboprop airliner being a notable money spinner for its manufacturers. Unfortunately, there were few others like it until perhaps the BAC 111, Avro 748 and de Havilland DH125 came along a decade or so later. Armstrong Whitworth’s AW 55 Apollo airliner, an elegant turboprop with four Armstrong Siddeley Mamba engines was designed for much the same market as the Viscount. Unfortunately, the Apollo did not enjoy the Viscount’s success and only two machines were built, plus one static fatigue test airframe. The Mamba proved to be an unreliable engine which left the Apollo distinctly underpowered. Perhaps with alternative power plants the Apollo may have fared a little better. One immediately thinks of the Rolls – Royce Dart as being a much better engine, although its installation may have proved problematic in the Apollo. This inability of Armstrong Whitworth, along with others, to design and build commercially successful civil aeroplanes, as an adjunct to their military aircraft, was to have serious consequences for the future.

Furthermore, being an acclaimed designer of military aircraft did not necessarily guarantee success in the civil aviation market. Roy Chadwick, the celebrated designer of the wartime Avro Lancaster, was less than accomplished with his Avro Tudor and Avro Tudor II airliners. These proved for various reasons to be extremely unsatisfactory passenger aeroplanes, and woefully unfit for airline service. The prototype Avro Tudor II crashed on take-off from Woodford on 23 August 1947, killing Chadwick and three other key Avro personnel, who were also on board. Although the crash was attributed to crossed aileron controls, a near criminal dereliction of someone’s duty, the aeroplane was really a turkey!

The one highlight of the immediate post-war British civil aviation scene appeared to be the de-Havilland Comet airliner. This advanced aeroplane was the world’s first turbojet powered airliner, complete with pressurised cabin and thus able to fly above adverse weather. The Comet promised advanced passenger comfort, free from the noise and vibration of piston engines; its economic success in International civil aviation market seemingly assured. However, sometimes it does not always pay to be the first, especially in high-risk, high-tech situations.

A Comet 1 with the British registration G-ALYP entered commercial airline service with BOAC on 2nd May 1952, to much national and international acclaim, heralding a new age for air travel. After a short interlude the crashes started. In the first two crashes each of the Comets failed to become airborne on take-off and initially these accidents were attributed to pilot error. However, it was found that certain factors, including high rotation, could combine to give a failure to lift from the runway. Modifications were incorporated into the Comet’s wing leading edge, and wing fences were also added to prevent span-wise air flow. Alterations were also made to the pilots’ take off notes. Later, another Comet crashed in a tropical storm with hints that structural failure could have been a factor. In 1954 a Comet disappeared over the Mediterranean, and shortly afterwards another was lost off the Italian coast. This resulted in the entire BOAC Comet fleet being grounded. The Ministry of Aviation ordained that instead of its own Accidents Investigation Board examining the crashes, as would normally be the case, the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough would be given the task.

The RAE used a large static water tank to subject a Comet fuselage (G-ALYU) to repeated cycles of pressurisation, depressurisation and over-pressurisation, simulating in service conditions. Eventually, a fatigue crack developed from a bolt hole forward of the port escape hatch in the cabin area and ran horizontally along a stringer. In flight this would have led to a catastrophic failure. This then was the cause of the Comet losses – a classic case of metal fatigue – the fear of all aircraft designers. Failure had occurred at 3,057 cycles, a figure somewhat lower than anticipated by the design engineers. Salvaged wreckage from the Comets that crashed in the Mediterranean also tended to confirm the static water tank test conclusions. The square shaped windows gave particular cause for concern as well as the type of riveting surrounding them. De Havilland’s used a peculiar form of countersink riveting called spin dimpling, used on thin skins, rather than the more normal cut countersinking on thicker material. Spin dimpling, because it is a forming operation rather than a cutting operation, has the propensity to propagate cracks. The author did a very limited amount of spin dimpling at AWA during his apprenticeship, and considered it a process that should have been reserved for the manufacture of pots and pans, but certainly not aeroplanes!

The solutions to the Comet’s ailments included some of the following; thicker skins, increased structure around the windows and other apertures, more generous radii in the window corners; improved riveting techniques, particularly surrounding the windows, and a general strengthening of the airframe. However, all this took time to design, engineer and incorporate into the Comet. Time was not on de Havilland’s side and Boeing and Douglas in the US were knocking on the door with respectively their 707 and DC 8 airliners. Any technical or commercial lead had been eroded. Britain very generously made the hard earned technical information from the Comet crashes freely available to all; very creditable, but not exactly calculated to give one a commercial edge!

When the Comet 4 finally recommenced airline service the competition, in the form of the Boeing 707, was firmly established in the market place. The Comet 4 was virtually a new aeroplane, benefitting from the Comet 1 crashes, but hamstrung by a terrible legacy and leapfrogged by the opposition. The author of this paper still considers the Comet 4, in its splendid BOAC livery, the most beautiful of all flying machines; never surpassed for its sheer elegance, but seriously compromised by its dark past. The author made only two flights in Comet 4s, operated by Dan Air London, originally ex-BOAC machines. Those were the days when one could go up to the flight deck, sit and chat with the crew and watch what was going on!

And so the 1950s rolled on with the Farnborough Air Shows exhibiting annually the latest and best British aircraft to thousands of enthralled spectators. How the author loved going with his father to those Farnborough public days; on specially organised rail excursions with coaches laid on to convey the crowds from Aldershot station to Farnborough itself! Every year there were new aircraft; experimental machines such as the Fairey Delta 2, flown by the redoubtable Peter Twiss, the first aeroplane to attain 1000mph and world absolute speed record holder, together with embryo fighters such as the P1A and P1B. However, these halcyon days of the British aircraft industry were about to be curtailed; the 1957 Sandys Defence White Paper was looming!

Duncan Sandys was the Minister of Defence in 1957, when in April of that year he produced his notorious White Paper on the future of the Royal Air Force, and by extension that of the British aircraft industry that served it. Sandys had earned his spurs in the latter part of the Second World War organising Britain’s defences against the German revenge weapons, V1 and V2. Therefore, he rather inclined towards rockets and guided missiles. Basically, his White Paper stated that apart from the English Electric Lightning fighter, which had gone too far in its development to be cancelled, there would be no more manned aircraft in the RAF; its future roles being performed entirely by missiles. The nuclear V bomber force would continue in service until it was replaced by intercontinental ballistic missiles, but that was it. This crass, ill-thought-through, cack-handed policy was to have disastrous consequences for the entire British aircraft industry.

Among the first casualties were those companies who had not managed to develop aeroplanes for the civil market. The Gloster Aircraft Company was a case in point. Apart from a few Schneider Trophy racing seaplanes, they had in their long and distinguished history only produced military aircraft, and consequently were to be badly affected by the Defence White Paper. Their “thin wing” Javelin replacement was cancelled. Saunders-Roe, based on the Isle of White, was also to suffer badly as their high performance interceptors, the SR 53 and SR177, both in prototype form, were also axed. Armstrong Whitworth had its projected AW169 Interceptor Fighter equipped with the Red Dean air to air missile cancelled, as did Fairey Aviation with its own contender for the same specification.

The Sandys edict did have the effect of forming alliances within the industry and this could be viewed as being both positive and long overdue. Aeroplanes were becoming increasingly expensive to design, develop and manufacture and very few individual companies had the wherewithal to accomplish it. The Hawker Siddeley Group had existed from well before the war and comprised not only airframe manufacturers but industrial companies, such as High Duty Alloys and Crompton Parkinson, etc. The airframe manufacturers in the Hawker Siddeley Group comprised: A V Roe, Armstrong Whitworth, Gloster Aircraft, Hawker Aircraft and subsequently de Havilland Aircraft Limited. It constituted just over half of the British airframe capacity.

On July 1st1960 another airframe grouping came into existence, this being the British Aircraft Corporation, comprising the Bristol Aeroplane Company, English Electric and Vickers Armstrongs. Westland Aircraft formed a smaller airframe grouping with Saunders -Roe and Fairey Aviation. Short Brothers and Handley Page both remained independent.

On the aero- engine side Bristol Engines Division amalgamated with Armstrong Siddeley Motors to form Bristol – Siddeley Engines Limited. Rolls Royce remained a separated entity until it absorbed the Bristol- Siddeley grouping at a later date. That left Napiers and de Havilland Engines as separate aero engine builders.

Glosters, who had been particularly hard hit by the Sandys White Paper, struggled on for a few years until they were absorbed by Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft, becoming Whitworth Gloster Aircraft on October 1st 1961. Gloster ended its days making special tanker vehicles and Automatic Vending Machines, an ignominious end for a once great aircraft manufacturer.

Although Armstrong Whitworth (AWA) had absorbed Gloster Aircraft to form Whitworth Gloster Aircraft, things were not completely satisfactory at Coventry. In an attempt to obtain some insurance against the vagaries of government military procurement, as demonstrated in the Sandys Defence White Paper, AWA in the late 1950s had, at their own instigation, embarked on the design of a civil transport aeroplane designated the AW 650 Argosy. A considerable amount of market research had indicated that there was a need for a medium range transport aircraft designed for rapid turn-rounds of palletised cargo.

To permit simultaneous loading and unloading of cargo from the front and rear of the AW 650s large freight hold, a twin boom, four engine arrangement was selected. The power plants chosen were the well proven Rolls – Royce Dart turboprops with provision for water methanol injection, permitting high temperature operation from elevated airfields. An initial batch of ten AW 650 Argosy 100 series civil freighters was laid down. These machines went to various customers, predominantly in the United States, where some were used on Military Air Transport Service (MATS) operations.

AWA realised that the AW 650 civil transport, with certain modifications, could be adapted for military use. The military freight version was allocated the designation AW 660. In place of the front and rear side opening fuselage freight doors as used on the AW 650, the AW 660 had a fixed front fuselage with “clam shell” or “beaver” doors at the rear; the lower half door serving as a vehicle ramp for access to the fuselage. The cargo floor was strengthened and military rated Rolls-Royce Dart turboprops were fitted. A weather searching radar was fitted to the nose, protected under a thimble radome. Fifty-six AW 660 C Mk I Argosy aircraft were ultimately built.

Although the AW 660 was a fairly satisfactory aeroplane, it was deficient in a number of respects, primarily in range and headroom in the cargo hold. Provision was made within all the AW 660s for in-flight refuelling, but only a few machines had the probes actually installed. The design team well understood these problems and tried to interest the Air Ministry in a revised specification, designated AW 660 Series 3, before the actual manufacture of the AW 660 C Mk I commenced. The Air Ministry showed no interest and elected to opt for the AW 660 C Mk I. Therefore, the RAF got an inferior aeroplane!

Meanwhile, the Air Ministry had been working on revised specifications for the next generation of RAF transport aircraft. The new machine would replace the ageing Hastings and Beverley transports. These plans were developed into Operational Requirement OR 351, for a turbojet powered transport with STOL/VTOL capability. AWA tendered for the OR 351 specification and after a rather protracted period won the design competition with their AW 681 proposal, albeit against strong opposition from the British Aircraft Corporation. A contract to proceed was granted on the 5th March 1962.

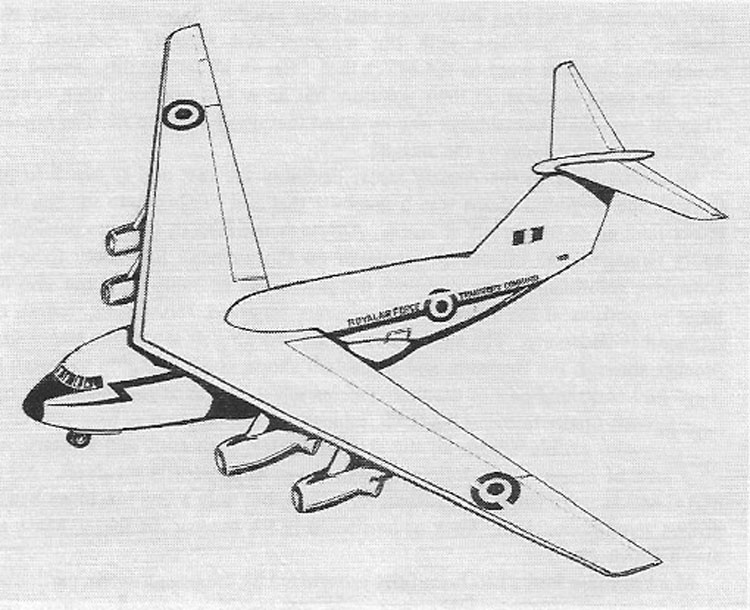

Operational Requirement 351 specified a STOL (Short Take Off and Landing) capability with a minimum load of 35,000 lbs. Provision was to be made to carry 60 fully equipped para-troops. The engine selected for the AW 681 was the Rolls-Royce RB 142 Medway, featuring vectored thrust, blown air for boundary layer control and blown flaps. The AW 681 featured a shoulder-mounted swept wing with the four Medway engines suspended beneath in pods. A high “T” tail plane completed the empennage. At the rear of the fuselage a ramp type access door facilitated vehicular access to the cargo hold. The main undercarriage was to be housed in blisters either side of the fuselage.

As with most specification drawn up by the “pipe dreamers” in the Air Ministry/MOD and RAF, the “Lilly became gilded”. In addition to having a STOL capability, the OR 351 specification had a supplementary requirement for VTOL (Vertical Take Off and Landing) added. This radically changed the complexion of the aeroplane and additional conceptual design work had to be done to provision for the vertical lift engines/and or vectored thrust. It was maintained that this was feasible! In the authors humble opinion, both then and now, it was a ridiculously unachievable requirement. Sixty years have elapsed and in that time no transport aircraft in the world, other than perhaps helicopters, has lifted itself vertically off the ground carrying a payload of substantial proportions (15 tons minimum in the case of the AW 681). One just wonders about the technical ability of the people employed by the MOD at that time!

A mere two seconds of thought by a few clever people in the Air Ministry should have concluded that the provision of additional vertical lift engines equalled extra weight incurred for mostly redundant lift engines, equalled extra fuel for mostly redundant lift engines, equalled extra fuel capacity for mostly redundant lift engines, equalled extra wing structure for increased fuel capacity for mostly redundant lift engines, equalled extra weight for totally overloaded aeroplane that could not get off the ground, vertically or any other way! “There’s a hole in my bucket Dear Liza”.

Nevertheless, despite these vicissitudes work started in the Baginton and possibly Whitley design offices on the AW 681. The author can remember the plimsoll shod loftsmen crawling over their horizontally mounted lofting tables using beam trammels with precision to lay out the profiles of the new aeroplane. These, however, were highly restricted areas and usually there was a security policeman at the entrance to the design offices, preventing unauthorised access. The author had no right to be there, so any glimpse of the work going on was fleeting!

The use of loftings for laying out the lines of a new ship on a lofting floor is a centuries old practice. In more recent times it was also used for aircraft. With the introduction of computer aided design and other modern techniques it is almost certainly not now used for aircraft, but over sixty years ago loftings were an important stage in the creation of a new design. The author very rarely came into contact with loftings, except that he remembers using one for a limited period in the construction of one of the Argosy boom frames that carried the water methanol tanks. They were useful for checking skin lines/profiles and on occasions could be more beneficial than jigs or fixtures, as they tended to show the relationship of all parts in a given assembly. They were rather like building a model aeroplane over a very accurate drawing!

Another important stage in the manufacture of a new aeroplane was the mock-up. This was usually a full-size representation of the aeroplane created in wood to convey the general arrangement of the machine with all the essential features in their correct relationship. Perhaps even more importantly, the mock-up showed the installation or housing of key items such as engines, armament, bombs, gunsights, hydraulic power-packs, undercarriages, etc, etc. Ministry officials liked mock-up conferences, as it allowed them the opportunity to get out of their stratified ivory towers in the Ministry of Defence to see some real work being done, and to check the taxpayer’s money was not actually being wasted. In the author’s opinion they themselves were the biggest wasters of public money, usually incurred in the cancellation, at huge cost, of aircraft projects at a very advanced stage! Many books have been written on Britain’s ministerial ineptitude regarding the aircraft industry, post 1945. The author of this paper could certainly write another one!

The AW 681 mock-up was constructed at Baginton in a corner of the old Bristol 188 shop. The author remembers seeing it several times, although due to security restrictions it was built behind screening. Nevertheless, over the months the distinctive shape of an aeroplane started to emerge. It is a long time ago, but the author of this paper seems to recall that the mock-up aircraft did not give the impression of being that large, but perhaps the wings had not been attached at that stage.

Readers well may ask why a particular shop at Baginton was named after a Bristol designed aircraft. The explanation is quite simple. In the 1950s The Bristol Aeroplane Company designed and built two high speed research aeroplanes, (plus one static test airframe), constructed predominantly of stainless steel. They were designated the Bristol 188. The reason for the selection of stainless steel as a construction material was its ability to withstand the high outer skin temperatures likely to be encountered at the sustained high speeds envisaged for the 188. Basically it could soak up heat. Stainless steel is a very truculent and difficult material to work, requiring special tools and equipment. It is definitely not like working with aluminium or magnesium, the more common aircraft construction materials. It took an inordinate amount of time to build two flight aircraft and the static test airframe. Years in fact! The Bristol Aeroplane Company enlisted the help of AWA and some of the work, particularly on the engine nacelles, was done at Baginton in the 188 shop.

The author recalls, as an apprentice, a college lecturer once relating how he had been involved with the Bristol 188 project whilst he had been an apprentice at Baginton in the 1950s. The lecturer, whose name the author still remembers with a degree of fondness, stated that every hole laboriously drilled in the stainless steel had to be microscopically examined for evidence of cracks. Not a very intelligent or practical way to build aeroplanes. A special welding technique was also developed for stainless steel called puddle welding. This was not entirely successful. The pair of experimental Bristol 188 research aeroplanes never attained their intended high speeds and they were not a great success. The 188 episode did probably teach the Bristol Aeroplane (BAC) designers and engineers one valuable lesson – not to build the future Concorde in stainless steel! By cleverly keeping the Concorde airframe just within the bounds of aluminium capability, Bristol (BAC) and Sud–Aviation (Aerospatiale) saved themselves a lot of trouble and strife! When the Americans very briefly entered the supersonic airliner arena, to counter Concorde, they elected to use titanium alloys for construction, and came unstuck in doing so! It’s nice to know the Yanks get things wrong too – occasionally!

We are now moving to the conclusion of our story. In 1964 a new Labour administration came into power and one of their first acts was to review certain aspects of defence spending. The review included key aerospace projects such as the British Aircraft Corporation’s TSR2 aircraft and Hawker Siddeley‘s P1154 Supersonic VTOL fighter and the AW/HS 681 STOL transport. Early in February 1965 the two Hawker Siddeley projects were cancelled and a pending decision held over on the TSR2. The cancellation of the TSR2 was concealed within the Budget Speech delivered on April 6th 1965.

Acres of print and much discussion were expended on the cancellation of the TSR2 aircraft, but very little in comparison was said about the two other axed aerospace projects. However, it was really a disaster for the entire British aircraft industry. The reason for the prominence of TSR2 in the national debate was not difficult to find. It was an aeroplane that existed and had been flown for some time, and what’s more gave every impression of meeting or exceeding its design brief. The other two projects had barely gone beyond the initial design stage, although there is no reason to believe they would not have been equally as successful in their own particular theatres of operation.

The effect upon Armstrong Whitworth, (Avro-Whitworth/Hawker Siddeley Aviation, call it what you will) was fairly immediate. The AW 660 military Argosy programme was winding down and the AW 650 Argosy 200 Series aircraft was not a commercial success and could not alone sustain a plant the size of Baginton, with all its multitudinous departments and functions. Something was going to have to give. And it did! Baginton was scheduled for closure. This was not an immediate act but slow and progressive and the factory gradually emptied as work was completed.

As has been noted previously in this paper, it was a case of pigeons coming home to roost. Armstrong Whitworth had been a very successful and efficient manufacturer of military aircraft over many years, but just like Glosters it had not bought an insurance policy in the civil aviation market for the rainy day when a less than friendly government withdrew its military largess.

The postscript on the Labour government’s actions was that after the cancellation of TSR2 it was ordained that all jigs, fixtures, special tools and equipment used in the manufacture of the aircraft were to be destroyed, ensuring there would be no Phoenix arising from the ashes. At least one of the TSR2 airframes ended up on the Shoeburyness gunnery range, used by the Army for target practice. A telling final act of how the British Labour government actually thought about its own aircraft industry! Rather strangely the first prototype Bristol 188 (13518) also ended up as target material at Shoeburyness. Altogether an extremely expensive multi-million pound taxpayer funded shooting gallery!

To replace TSR2 the Labour government was keen to purchase from the United States the General Dynamics F-111 variable geometry wing, multi-role combat aircraft, on the basis that it would be cheaper than the home grown product. Perhaps fortunately, although not without considerable cost to the taxpayer, this contract for the F-111 too was cancelled. The Australian government had purchased the F-111 and experienced considerable trouble with it, so perhaps there was a silver lining of sorts. The irony is that the variable geometry wing, as used on the F-111, was actually a British invention from the brain of one Dr Barnes Neville Wallis of Bouncing Bomb fame!

Having cast aside the AW 681 transport with its STOL and doubtful VTOL capability, the government purchased from the Americans the Lockheed-Martin C130 turboprop transport aircraft. This was a low risk choice of an established and perfectly satisfactory aeroplane. But it was not turbojet powered and it was not what the Ministry of Defence and the RAF had demanded with its specification for OR 351! So who were people who cost the country millions of pounds in contractual fees on cancelled aircraft, lost jobs and the complete destruction of an industry employing highly skilled people? Was it the politicians, the Whitehall mandarins, the MOD or RAF Service Chiefs? Take your pick- the author thinks they were all culpable, perhaps in equal measure, but for possibly quite different reasons.

Not one example of an AW/HS 681 exists because none were built, and save only for possibly a few models and artists’ impressions there is nothing at all to show for considerable human endeavour at AWA Coventry.

Two TSR2 aircraft still exist in Museums; one at Duxford and the other at RAF Cosford. The second prototype Bristol 188 (13519) is also exhibited at Cosford.

References:

- Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft, The Archive Photographs Series, Compiled by Ray Williams, Chalford Publishing, 1998

- Empire of the Clouds, James Hamilton- Paterson, Faber and Faber 2010

- I Kept No Diary, FR (Rod) Banks, Airlife, 1978

- The Rise and Fall of Coventry’s Airframe Industry, John Willock, WIAS Publication

Copyright © J F Willock August 2020

This silent films shows a designer highlighting some of the aircraft’s features including the VTOL concept