The Armstrong Whitworth AW 38 Whitley Bomber

This paper is a brief history of the AW 38 Whitley Bomber designed and manufactured by Sir WG Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft Limited, Coventry.

During its long history of aircraft manufacture, Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft (AWA) built a great variety of aeroplanes for both civil and military purposes. Some of the aeroplanes constructed at Coventry were to the company’s own designs and others, notably the Avro Lancaster and Lincoln, Gloster Meteor and Javelin and Hawker Hunter were designed elsewhere by other constituent member companies within the Hawker Siddeley Group.

Perhaps the most renowned of all AWA designs and named after the district in Coventry where the company had its first major factory, the AW 38 Whitley Heavy Bomber was used by the Royal Air Force in the early years of the Second World War.

The Whitley was an aesthetically unappealing aeroplane that made no pretence to good looks; every feature of its construction being subordinated to ease of manufacture. When looking critically at the Whitley today it should be remembered that upon its introduction into the RAF it was replacing obsolescent biplane bombers such as the Handley Page HP 50 Heyford; machines little changed from those used in the First World War. Therefore, at the time of its inception the Whitley was a big step forward, both in design and methods of construction.

The origins of the Whitley can be traced back to its immediate predecessor the AW23; a twin engine bomber and transport aircraft designed to Air Ministry specification C26/31. This aircraft had two important technical features that were to be subsequently incorporated into the Whitley. They were a box-spar type wing and a retractable undercarriage. Otherwise the AW 23 did not make much of a mark on aviation history, apart from some pioneering work on in-flight refuelling.

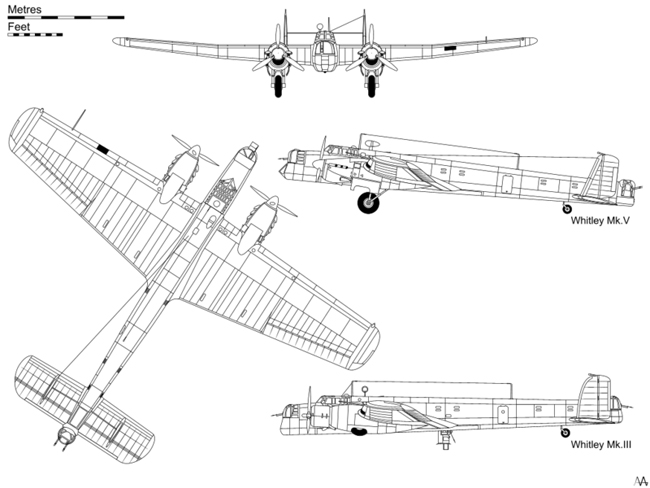

Designed by AWA’s Chief Designer John (Jimmy) Lloyd to Air Ministry specification B3/34 for a night bomber, the AW 38 Whitley was a twin engine monoplane substantially of metal construction, featuring a box spar wing, retractable undercarriage and turreted defensive gun positions in the nose and tail. Provision was made within a later specification (B20/36) for a retractable ventral “Dustbin” gun turret to be fitted, although this incurred so much drag in the extended position that in service it was little used and was later removed. However, the circular floor mounting ring for the turret was retained throughout the life of the Whitley and subsequently used for other purposes.

AWA had long been pioneers in metal aircraft construction and used these methods to good effect in the manufacture of the Whitley. Wherever possible standard aluminium rolled sections and extrusions were used to facilitate ease of manufacture. In particular AWA had pioneered “blind” riveting techniques, notably the use of the “pop” rivet. These enabled structures to be riveted up from one side only, obviating the need to “dolly up”, as would be the case with conventional solid riveting methods. “Pop” rivets could be set by using either manually operated “Lazy Tongs” or compressed air/hydraulic intensifier tools.

The box spar type of wing construction was to confer huge strength on the Whitley and consequently this enabled it to sustain serious battle damage, a quality that would be essential in the forthcoming conflict. The flat sided fuselage comprised three sections, each of semi-monocoque construction, using frames and stringers skinned with aluminium “Alclad” sheeting.

When the Whitley prototype first flew, retractable undercarriages were very much a novelty in the RAF. This was borne out by the fact that Britain’s front line fighter, the Gloster Gladiator biplane with fixed undercarriage, was only just entering Squadron service in July 1936, some months after the Whitley prototype had first flown!

Wing flaps were not a universal feature on aircraft when the Whitley was first conceived and the two prototypes did not have these flying controls fitted. To compensate for the lack of flaps and ensure satisfactory landing speeds, the angle of incidence at which the Whitley’s wing was set was therefore relatively large. The angle of incidence may be defined as the included angle between the aircraft’s horizontal centre line and a line drawn through the wing’s aerofoil section, connecting the leading and trailing edges, called the Chord Line.

In normal level flight the Chord Line through the wing aerofoil section dictates the attitude the aircraft as a whole will adopt in the air. With the angle of incidence on the Whitley being quite large, in the order of eight degrees, this meant that there was always a pronounced nose down attitude to the Whitley’s line of flight. Although flaps were subsequently incorporated into the Whitley’s wing, the angle of incidence remained unchanged and consequently the Whitley retained its nose down flying attitude right to the end of its life! Also, the engine thrust lines, together with the slab-sided fuselage and thick angular wings gave the aircraft an ungainly look in the air, and it was almost inevitable that the Whitley would be dubbed the “Flying Barn Door”.

At the newly built Coventry Baginton factory two AW38 Whitley prototypes were constructed in parallel, with the sequential registration numbers, K 4586 and K 4587. The first prototype was equipped with two supercharged Armstrong-Siddeley Tiger IX, fourteen-cylinder, two-row radial engines, installed into wings with no dihedral. On 17th March 1936 the first prototype K 4586 made it maiden flight from Baginton, with AWA’s Chief Test Pilot A C Campbell-Orde at the controls. The second prototype, K 4587, was powered by higher rated Tiger XI engines and included the addition of dihedral on the outer wing panels, to correct some instability that had been detected in the first prototype and early production machines.

In placing the Whitley in context with its aviation contemporaries, the Hawker Hurricane prototype (K 5083) had first flown on 6th November 1935 and the Spitfire prototype (K 5054) on the 5th March 1936. These successful maiden flights of new machines must have given considerable encouragement to the Air Ministry and service chiefs that at long last the RAF was on its way to obtaining modern aircraft to re-equip its obsolescent fighter and bomber squadrons.

Number 78 Squadron at No. 10 Heavy Bomber Group based at Dishforth, Yorkshire was the first operational unit to receive the new Whitley B1 bomber in 1937. Due to shortages, the first aircraft delivered to the RAF were minus their front and rear gun turrets, and the machines were supplied with their respective defensive positions faired over. Early marks of the Whitley had AWA’s own design of manually operated gun turrets. These were clearly unsatisfactory and with the introduction of later marks of aeroplane, Nash and Thompson hydraulically powered turrets were introduced. The hydraulically powered rear turret of a Whitley packed quite a powerful “sting” and with its four 0.303” Browning machine guns it was probably the best protected British bomber in 1939.

Although the French had conceived the idea of the two-speed aero engine supercharger, Armstrong-Siddeley was among the first to actually introduce this new development into their Tiger VIII radial engine, raising its output to 845 hp. The Whitley became the B II with these engines installed. Another engine under development by Armstrong-Siddeley was the unique 21-cylinder, three-row, air-cooled radial of 38.2 litres capacity, named the Deerhound. Featuring overhead camshaft drives for the poppet valves and a two-speed supercharger, this exciting engine incorporated many new ideas. The Deerhound was experimentally installed in Whitley B II, K 7243, and featured very closely cowled engine nacelles and large streamlined propeller spinners; altogether a very neat installation indeed.

Whitley K 7243, with its two Deerhounds, first flew on 6th January 1939 and some problems were initially encountered with the overheating of the rear row of cylinders. A redesign of the cowling seemed to cure this problem. Unfortunately, on 6th March 1940, this aircraft crashed during take-off from Baginton, killing all the Armstrong-Siddeley test personnel on board. It is recorded that this accident was not attributable to the engines and may have been caused by a faulty elevator trim.

In 1941, under instructions from the Air Ministry, all development work on the Deerhound ceased. Given time the Deerhound and its projected larger successors, the Boarhound and Wolfhound, might have been developed into truly great engines; however, we will never know. One example of the Deerhound apparently survived until the 1970s, but was then unfortunately scrapped. Surely as late as the 1970s it could / should have been possible to save this very rare engine for a museum? Is this a very late example of corporate/ institutional vandalism?

At the outbreak of war in September 1939, the RAF had at No 4 Group, six operational squadrons of Whitley bombers. On the first night of the war ten Whitleys from Leconfield dropped 13 tons of propaganda leaflets on selected targets in Germany. These incursions were to continue for some time until it was eventually realised by the government that they were a fairly valueless exercise, needlessly endangering both aircrew and valuable machines. They were not popular operations and were referred to as “Bumphlet” raids by those who undertook them.

The inherent strength of the Whitley structure was demonstrated on the 28th November 1939 when a Whitley B V, N 1377, was struck by lightning whilst in flight. Both wings were virtually denuded of their metal skinning, but despite this Pilot Officers Gray and Long nursed the badly damaged Whitley back to their station at Bircham Newton. For this act of conspicuous bravery both Officers were awarded DFC’s.

The Whitley was always decidedly underpowered with the Armstrong-Siddeley Tiger engines, and it was decided to re-engine the airframe with the Rolls-Royce Merlin. A Whitley B I (K 7208) went to Rolls-Royce Hucknall for this installation work to be carried out, probably in early 1938. After a number of recommendations by the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A & A E E) the Merlin Mk IV of 1,030 hp was found to be satisfactory and this engine was passed for service in the Whitley. With this engine the Whitley was designated the B IV.

When powered by the uprated Merlin X engine the Whitley became the B V, the most numerous of the mark. In addition to the new engine, a 15inch extension was added to the rear fuselage permitting an increased field of fire for the rear gunner. The twin tail fins were also redesigned and a de-icing system was installed on the wing leading edges. The first B V (N 1345) made its initial flight on 4th August 1939, with AWA’s Eric S Greenwood at the controls. Ultimately a total of 1,466 Whitley B Vs were produced.

AWA was under considerable pressure from the Air Ministry and subsequently the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) to produce the Whitley in volume. In May 1940 the MAP, then under the direction of Lord Beaverbrook, decided to allocate “top priority” to only five major aircraft types. One of the selected “priority” aircraft was the Whitley. Thus AWA became one of the most important aircraft manufacturers in the country. In his tenure at the MAP, Beaverbrook was always hectoring the aircraft industry about production targets and AWA was no exception. Some of Beaverbrook’s letters to Mr HM Woodhams, AWA’s manager during the very critical war years, are reproduced below. With their brevity and terseness they convey the sense of urgency of the period. However, Beaverbrook’s letters occasionally could be complimentary!

One letter to HM Woodhams dated 25th August 1940 stated;

“Dear Mr Woodham,(sic)

The report shows you did not work your plant from Saturday evening until Sunday night. No doubt there is some good reason for this. But I should like to know it. We want all the production we can get now, particularly from key factories such as Armstrong Whitworth.

Yours sincerely, (signed) Beaverbrook “

Another from Beaverbrook dated 4th September 1940 read;

“Dear Mr Woodham,(sic)

I constantly hope that manufacturers will exceed the production programme. I regard it as a minimum upon which they can build greater things. I am disappointed to see that Armstrong Whitworths (sic) can only produce 39 Whiteleys (sic) during August against a programme of 40. But I am sure that the September figures will show a great improvement. I have every trust and confidence in the efforts you will make.

Yours sincerely

(signed) Beaverbrook”

And finally a letter dated 27th February 1941 stated;

“Dear Mr Woodham,(sic)

I hasten to pass on to you joyful tidings which have just reached me. Your works at Baginton have been selected as one of the key aircraft works at which a permanent guard of one fighter aircraft will be stationed. The duties of this machine and its pilot will be confined to protecting the works against an attempt by the enemy to attack it from the air. And I am confident that your workforce will rejoice with me in a substantial addition to the defence of the factory. Much depends on their labours for the Royal Air Force. Now the Air Force intervenes to increase the security in which those labours are conducted.

Yours sincerely (signed) Beaverbrook”

For a newspaperman these are hardly journalistic or literary masterpieces, but they do convey the basic sense of urgency at a critical stage in the war. Beaverbrook’s secretary also made a few errors, but I expect working for such a taskmaster she (he – doubtfully) was under considerable pressure too!

Probably because of AWA’s importance to the war effort, it was almost inevitable that Prime Minister Winston Churchill would make a visit to Baginton. This actually took place on Friday 26th September 1941. It was a visit viewed with some apprehension by Churchill’s Secretary, John Colville (later Sir John Colville). He confided in his diary for that day:

“We toured the Armstrong Siddeley factory, where aircraft parts and torpedoes are made, and the PM had a rousing reception………. The Whitley bomber factory is a hotbed of communism and there was some doubt of the reception the PM would get.”

In fact Colville went on to record that Churchill did receive a good reception at Baginton, although he concludes his diary note by stating that full Whitley production was not achieved until after the Soviet Union had entered the war.

The author considers Colville’s comment is a little too simplistic and fails to take account of the many factors in play in the aircraft industry under wartime conditions. The aircraft industry had been required to expand very rapidly due to the threat of war and had taken on thousands of largely unskilled employees, including many women, who had to be taught a whole new range of skills. It had also been necessary to change working practices and manufacturing techniques. All this took time to implement. Also, politicians had very conveniently forgotten that the aircraft industry had been starved of orders almost from the declaration of peace in 1918. Years of stagnation and lethargy had set in. Suddenly in 1939 the country wanted large numbers of modern military aeroplanes again ….. all in a trice!

Later that day, after leaving AWA at Coventry, the Prime Minister went to Birmingham to see Spitfire production at Castle Bromwich. At Castle Bromwich he was treated to a spectacular aerobatic display by Chief Test Pilot Alex Henshaw, perhaps the greatest exponent of the Spitfire. Therefore on the same day Churchill saw two vital but totally different military aircraft under construction in the Midlands; firstly the Whitley “Flying Barn Door” and secondly the ballerina – like Spitfire!

After the conclusion of the propaganda operations, the Whitley along with the Wellington and Hampden took the bombing offensive to Germany. These were difficult times for Bomber Command. The aircraft available were far from satisfactory and the crews relatively inexperienced. There were no navigational aids to assist the navigators to the target. Directional radio beams such as “Oboe” and “Gee-H”, to assist in bombing, were in the distant future. Therefore it was Astro Navigation, dead reckoning, intuition and a fair amount of luck that helped find the target – or not as the case may be. It is hardly surprising that bombs dropped in the early war years seldom got within 5 miles of the designated target. Nevertheless, these were times when deeds counted for more than rhetoric and the Whitley was up there, right at the very front taking the war to the enemy!

The Whitley had many “firsts” to its credit. These included:the first aircraft to drop bombs on German soil; the first aircraft to drop bombs on Berlin; the first aircraft to fly across the Alps and attack targets in Italy and the first aircraft in Coastal Command service to sink a U-Boat unaided. The Whitley because of its relatively good range also attacked industrial targets in Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland and participated in the first 1000 bomber raid on Cologne.

Apart from the bomber offensive, Whitley aircraft participated in several clandestine and airborne operations. It will be recalled that earlier in this paper reference was made to the “Dustbin” ventral turret that was subsequently withdrawn from service, leaving a redundant mounting ring in the fuselage floor. It was found that this ring, suitably modified, provided a means of egress in flight, and thus the Whitley performed a function for which it was never designed; that of para troop transport.

On the 10th February 1941 Whitley aircraft conveyed para troops participating in Operation Colossus to Italy, where the objective was the destruction of the Tragino aqueduct. This raid was accomplished with complete success. A year later on 27th/28th February 1942, Whitley aircraft of 51 Squadron carried “C” Company, of the 2nd Parachute Regiment, on the famous Bruneval raid. It will be recalled that this audacious operation had the objective of capturing a complete Wurzburg radar installation situated on the French coast, 18 km north of Le Havre. This operation was also a total success.

In April 1942 the Whitley was officially withdrawn from operations with Bomber Command, although the type did participate in the first 1000 bomber raid on Cologne on the night of 30th/31st May 1942. However, this was by no means the end of active service for the Whitley. Since the autumn of 1940 the type had been pressed into service as a maritime reconnaissance aircraft with Coastal Command and again because of its relatively good range, it was considered a suitable stopgap for this operational requirement. Whitley V machines were modified to accept the long range, Mk II Air-to-Surface-Radar, and when so equipped were re-designated the Whitley VII. A Whitley VII of No. 502 Squadron secured the first definite “kill” with the new radar, when a German submarine, U 206, was destroyed in the Bay of Biscay on 30th November 1941. Other roles undertaken by the Whitley included glider towing and freighting activities.

One final task that the Whitley undertook was that of freight carrier. This was a civilian role and the aircraft were registered accordingly; fifteen specially converted B V machines being operated by British Overseas Airways Corporation. Their duties included delivering urgently wanted supplies into beleaguered Malta and operating on the so called “Ball-bearing run” between Britain and neutral Sweden. By and large the Whitley was far too slow and vulnerable for these missions and they were soon replaced by much faster aircraft such as the Mosquito.

Production of the Whitley bomber terminated at Baginton on 12thJuly 1943, with the final and 1,814th machine being rolled off the assembly line. This aircraft, a B V registered, LA 951, was not actually delivered to the RAF but retained by the company as a test bed machine. LA 951 was subsequently used as the towing aircraft for the AW52 G Flying Wing Glider. (See authors WIAS paper on the AW 52 Flying Wing). It was scrapped in June 1949 and at that time was probably the last surviving Whitley.

In an otherwise authoritive work published some three decades or so ago it was suggested, without a scrap of verification, that AWA was considered a weak industrial organisation unfit to cope with a change in production type. The author of this paper suggests the facts tell a quite different story! Quite apart from manufacturing the Whitley during the war, AWA managed numerous factories across the midlands, including Baginton and Bitteswell, engaged in producing the Avro Lancaster bomber. In fact AWA produced the Lancaster in greater numbers than any other member of the Lancaster manufacturing consortium – with the sole exception of AV Roe itself! Additionally, AWA at Baginton also produced 300 Lancaster Mk IIs (“The Insurance Lancaster”) fitted with the Bristol Hercules radial engine, a type not manufactured by any other organisation, including AV Roe.

Towards the end of the war AWA re-tooled to produce the Avro Lincoln bomber, a development of the Lancaster. In 1944, at the direction of the MAP, AWA took over the management of Short’s Swindon factory manufacturing the Short Stirling bomber. One hundred and eight Stirlings were produced at Swindon whilst it was under AWA’s control. Therefore, at least four different major aircraft types were produced by AWA in a similar number of years. Those are the facts, hardly indicative of a weak industrial organisation unfit to cope with a change in production type!

Although not really part of the Whitley story, another military aircraft was designed by AWA in the years immediately preceding the Second World War. This was the AW41 Albemarle, a twin-engine general purpose aircraft designed to Air Ministry specification B9/38. Because of AWA’s heavy commitments with the Whitley, prototypes and production Albemarles were not built at Coventry. Gloster Aircraft at Brockworth was selected to build the Albemarle in volume and did so under a Hawker Siddeley Group contrived name – “AW Hawkesley Limited”. The Albemarle had the distinction of being the first aeroplane operated by the RAF with a tricycle undercarriage – very probably of AP Lockheed manufacture. Six hundred Albemarles were ultimately built by AW Hawkesley.

The Whitley was very much an aeroplane of its time, circa 1935/36, and was then in the forefront of contemporary aviation design and thinking. That technical lead was soon to be eroded and by the start of the Second World War the Whitley was obsolescent. Therefore, the Whitley was never going to be a really great aeroplane, but along with the Vickers Armstrong Wellington and Handley Page Hampden, it was the best that Britain had at the very start of the war. It doggedly took the early bombing offensive to Britain’s enemies and recorded many “firsts” in RAF service. Additionally, its ability to return home after sustaining serious damage was almost as legendary as that of the Wellington. Above all, it was available at a very critical time in the war, when there was nothing else capable of doing the job.

After some deliberation the author of this paper has decided to include a slightly amusing “Dad’s Army” postscript to the Whitley story. One day probably fairly early in the war, the author’s mother was walking with a friend down a road in Leamington Spa, not too far from the Automotive Products – Lockheed factory. They heard the drone of an aeroplane overhead and the friend, being wary, voiced the concern that it may be an enemy aircraft and they should go to the nearest shelter.

The author’s mother, who hadn’t a clue about aircraft recognition, declared that it was alright because it was a Whitley! The friend was still unsure and her fears were confirmed when the Lockheed defences proceeded to open up with withering anti-aircraft fire directed at the the unfortunate machine. The author’s mother stood her ground and declared it was a Whitley and the Lockheed were firing on “one of ours”. This soon proved to be correct as the pilot of the aircraft started to hurriedly discharge the coloured recognition flares of the day!

It is highly likely that AWA gave AP Lockheed quite “a rocket” over this incident. The Whitley was probably on a test flight from Baginton and very likely piloted by AWA’s Chief Test Pilot, Charles Turner-Hughes assisted by Eric Greenwood. Turner-Hughes resided in Lillington during the war years and would, therefore, have been very handily placed to deliver the admonition personally!

Ironically, the AP Lockheed factory was attacked on at least two occasions during the war by opportunist German raiders, seemingly without too much opposition from the defences. Perhaps the AP Lockheed Home Guard just didn’t like the look of Whitleys! Some would say who could blame them!

Not one example of the 1,814 Whitleys produced exists. A section of a Whitley fuselage, together with other fragments are on display at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry. It is the intention of a Whitley preservation group to rebuild a complete machine from available parts – a very considerable undertaking indeed!

Copyright © J F Willock August 2020

References:

- Aeronautical Engineering, Edited by RA Beaumont, Odhams Press, 1942

- Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft, The Archive Photographs Series, Compiled by Ray Williams, Chalford Publishing, 1998

- Bomber Command, The Air Ministry Account of Bomber Command’s Offensive Against the Axis, September, 1939 – July, 1941 London: HMSO

- Major Piston Aero Engines of World War II, Victor Bingham, Airlife, 1998

- Merlin Power, The Growl Behind Air Power in World War II, Victor Bingham, Airlife, 1998

- Sigh for a Merlin, Testing the Spitfire, Alex Henshaw, John Murray,1979

- The Rise and Fall of Coventry’s Airframe Industry, JF Willock, WIAS Publication