Early Wooden Railways

There is a tendency to think that railways were a nineteenth century phenomenon, the names of Trevithick, Blenkinsop, Hackworth and Stephenson, et al, being synonymous with their early development. However, this is a very incomplete view of the historical picture. Railways are in fact far older than the nineteenth century and in this country date back to the very early seventeenth century and long before that in Europe. These earliest railways were of course not constructed of iron and steel but solely of timber and were located primarily in coal or mineral mining areas. Horses or human physical effort provided the motive power for moving the wagons.

Documentary evidence for England’s first railway occurs between the dates of October 1603 and October 1604, when an individual named Huntingdon Beaumont leased and worked a number of coal pits in the Wollaton and Strelley/Bilborough manors of Nottinghamshire, owned respectively by Sir Percival Willoughby and Sir Phillip Strelley. Beaumont’s arrangement with the two landowners indirectly resulted in a railway about two miles long that conveyed Strelley coals through Wollaton, “alonge the passage now laid with Railes, and with suche or the lyke Carriages as are now in use for that purpose”.

The next reference to an English railway relates to Shropshire. Here the evidence comes from two lawsuits heard before the Star Chamber in 1606 and 1608. This concerned Richard Willcox and his associate William Wells v James Clifford, Lord of the Manor, over disputed way-leaves relating to the use of railways over Clifford’s land. It would appear from these particular lawsuits and other subsequent issues, between local landowners and mining entrepreneurs, that the introduction of early wooden railways to Shropshire was far from harmonious! Very recent research by Industrial historians in this particular field is tending to close the small gap between the Nottinghamshire and Shropshire dates.

The earliest wooden railways around the Broseley area of the East Shropshire coalfield would have been situated partially underground in shallow mine workings and partially on the surface. Railways on the surface facilitated the transportation of coals to the River Severn for subsequent shipment by trows downstream to major population centres such as Worcester, Gloucester and Bristol.

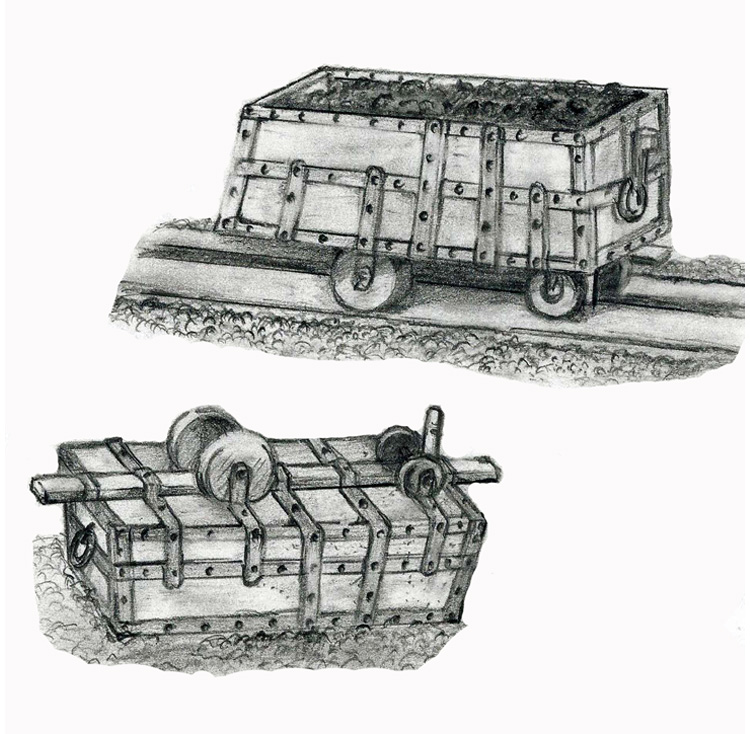

Although early Shropshire railways could perhaps be characterised as being small in gauge and crude in construction, they seemingly utilised from the outset the timber edge-type rail on which ran a flanged wooden wheel; a particularly neat and elegant engineering solution and the precursor for all subsequent railway systems. The person who actually conceived such a simple but effective idea will almost certainly never be known, but whoever they were they left a tremendous legacy for future rail transportation.

Madeley Wood Bedlam Furnaces in the Severn Gorge –

Sketch by author

The introduction of early railways into Shropshire and Staffordshire brought into the English language a whole new nomenclature. “Footrid” was used initially to define an open cast coal mine and inset, footrail, footridge, footroad, a horizontal drift mine and subsequently by extension all of these terms to describe a railway. A rid or ridding (ryddinge) was an opencast mine where it was necessary to “rid” the overlying soil, overburden, trees, etc, to obtain the coal. There are numerous references to riddings in midlands mining areas. Words such as “railway” or “railroad” were probably first coined in Shropshire or Staffordshire.

Early Continental European railways in mining areas such as the Vosges, Tyrol, Lower Hungary and the Harz mountains were somewhat older than their English counterparts and developed quite differently. They also utilised a bewildering variety of guidance methods for their wagons or hunds, none of which being particularly practical. One of these guidance methods featured a iron peg which projected from the underside of the wagon and engaged in a slotted member positioned between the “rails” or baulks of timber on which ordinary unflanged wheels ran.

Right – “Leitnagel Hund, Erzgebirge, Circa 1556. Sketch showing typical construction of an early continental wagon with projecting pin (nagel) method of guidance – Sketch by author after Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica, 1556”

Without too much difficulty it can be visualised that the slot would become filled with detritus and the task of pushing and guiding a wagon would become progressively more difficult. The flanged wheel system, although infinitely superior, was only adopted on the continent at a very much later date. One of the earliest representations of a miner seemingly pushing a wagon is featured in a stained glass window in Freiburg im Breisgau Cathedral, Southern Germany, Circa 1350. Whether this actually represents a railway wagon at this early date is uncertain. However, an illustrated tract printed in Lower Austria between the years 1515-38 shows a mining scene with a wagon wheel apparently running in a rail of channel section

The combination of the wooden edge rail and flanged wheel remained in service for many years until the first cast iron railway wheels started to be produced by the Coalbrookdale Company in I729. Thereafter wooden wheels were probably very quickly supplanted; the superior wearing qualities of the iron wheel becoming immediately obvious. In 1767 the Coalbrookdale Company introduced the world’s first cast iron rails. The earliest forms of cast iron rail sections were provided with lugs to allow them to be secured to the existing wooden rails with a minimum of operational disruption.

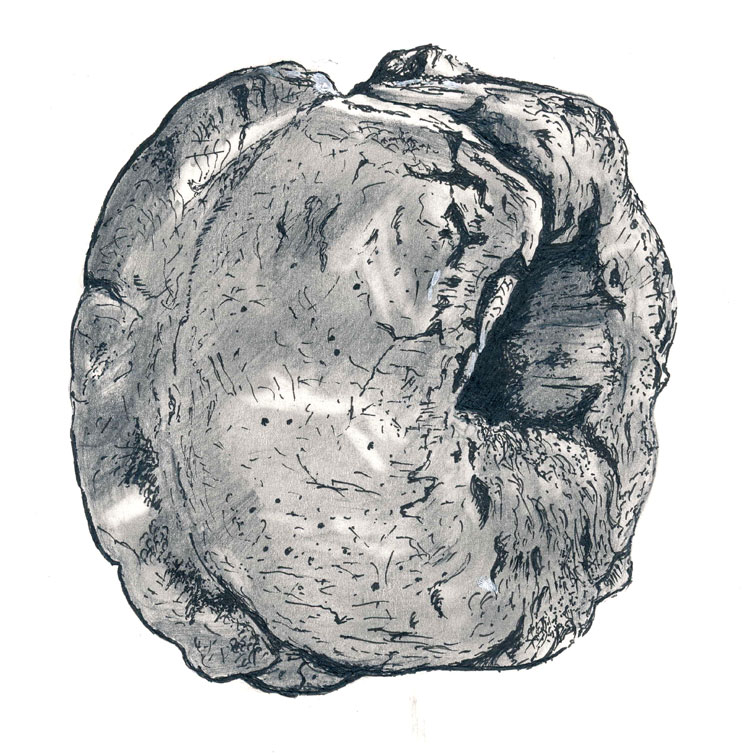

In about 1900 / 1901 the writer’s maternal great grandfather, who at the time was responsible for the operation of the Caughley (pronounced Carfley) Colliery in Shropshire, discovered some very old underground workings in the vicinity of the pit. From these workings he retrieved an old wooden flanged wagon wheel. Made from a single block of elm the wheel had split, probably early in its working life, had been repaired using metal staples and then split again. Apparently it had then been discarded, and this very act probably ensured its survival. The wheel’s age is uncertain. It could be of the seventeenth century, or early eighteenth century, but is unlikely to be much later than 1750. In more recent years the wheel was presented to the Ironbridge Gorge Museum for safe keeping. The author is pleased to advise that after years of residing in a filing cabinet the wheel is now on display!

Left – A drawing of the flanged wheel – overall diameter of the wheel, 9.5” (241mm) – Sketch by author

At various other times similar early flanged wooden railway wheels have been found in the Severn Gorge area, but these have either disappeared over time or just been lost. Therefore, the wheel found at Caughley and now on display in the Ironbridge Gorge Museum, is arguably the world’s oldest flanged wooden railway wheel. That is until another appears, which of course is quite possible!

As a footnote the Caughley Colliery was very near to the site of the Caughley Salopian Porcelain Manufactory, in operation from about 1775 – 1799, under the ownership of Thomas Turner. In its heyday the output of the works was large and rivalled that of the Worcester factory, making a very similar type of soft paste porcelain. After 1799 the factory was operated by John Rose. Upon its closure in 1814 the factory was dismantled and moved to nearby Coalport. The porcelain made by Turner at Caughley was of a generally fine quality, using a soapstone rock ingredient mined in the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall and brought by way of the River Severn to Caughley. Decoration of the finished pieces was accomplished using predominantly, although not exclusively, blue and white chinoiserie style under-glaze printed patterns pulled from engraved copper plates. Even today the Caughley site is remote. The reason for siting the porcelain works in such a location is simple – the abundance of readily available coal. It takes at least ten tons of coal to fire one ton of porcelain, so it is easier, cheaper and more expedient to bring the china clay, even from a distance, to the coal and not the other way round!

References:

- Early Wooden Railways, Dr MJT Lewis, Routledge and Keegan Paul, London, Paperback Ed, 1974

- An Ancient Wheel from Caughley, J Willock, Caughley Society Newsletter, No75, August 2018

- Caughley Blue and White Patterns, The Caughley Society, 2012

Copyright © J F Willock April 2021